Change management frameworks for major projects – and there are many flavors – have become so widely socialized in business that most companies take a rinse-and-repeat approach and redeploy them for subsequent projects. And why not? If companies are in a continual state of change, at least the change plan itself can seem familiar and reliable: Here’s how we do change here.

But what happens when companies that have undergone several cycles of change reuse a change plan that makes now-outdated assumptions about employees’ attitudes? The more that significant change happens, the more the mantra starts to turn into Here’s how we do change here – and there are always fewer jobs at the end.

Jobs are ALWAYS the third rail and the number one concern of employees in major changes and transformations. Companies that assume otherwise are jeopardizing their culture by squandering their credibility. I think what’s new in corporate life is that for employees anticipating the next major project, after undergoing waves of change over a few years, this becomes the ONLY concern. Nothing trumps it – not being seen as an effective change leader, not success in the post-change environment.

Adapting to new processes, relearning the org chart, reconfiguring data systems, merging or acquiring: fine, fine, been there, got the coffee mug. Employees become confident that change happens and learning curves are necessary and allowed. But they also understand that efficiency, streamlining, rationalization, productivity, or process improvement do not ADD headcount. They’ve never seen that once.

It’s impossible to believe in the strategic goals of a change project when it just feels like another round of Russian roulette.

As digitization and AI continue to drive economies in businesses, there’s no going back to a stable workforce. Employees get that, but they’re not sure that you get that they get it. What would a change and communication approach look like in the new world of work?

One possibility. I worked with a smart CEO who used his employee meetings to talk regularly about the challenges of the wider business environment in his industry area. He made sure people knew that he was just as subject to quickly emerging trends and demands as they were. He talked to employees as if they were owners or board members, and he didn’t sugarcoat reality. One of the effects of this was to equip people to think creatively about where and how they could add value, whether they continued with the company or not. It was an appeal to self-interest in a way that redounded to the company’s interests.

I believe this notion of setting a wider context needs to become more and more part of the messages about the changes themselves. If a business can’t be reassuring, then it can be honest. I think context could become the core of all project communications even to the extent of displacing project specifics – it should absolutely replace all of the “great new day ahead” messages that typically frame up these projects. The days of kicking off major transformation projects with offsite theme parties are probably—mercifully—over.

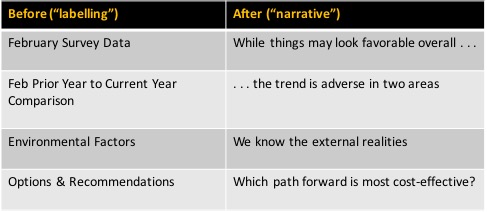

How can you change up the change plan to improve employee engagement?